Blending Pinot Noir and Syrah – The Backstory

While pinot noir and shiraz are not quite polar opposites, the thought of blending the two varieties together may seem shocking to many. However, in the 40s and 50s, one of Australia’s legendary winemakers made arguably some of our greatest and most enduring wines pairing just those two grapes.

While shiraz has been omnipresent in Australian wine history, occupying more vineyard land and a firmer grip on wine drinkers’ imaginations than any other variety, pinot noir has been in the ground here for just as long. For much of that tenure, though, its presence was a mere blip – a curio. And indeed, it was almost forgotten until the cool-climate revolution that took meaningful shape in the 1980s.

When the spotlight started to tilt in pinot noir’s direction – as regions such as the Mornington Peninsula, Yarra Valley, Adelaide Hills and the like started to find their stride – shiraz, or at least many traditional shiraz drinkers, took umbrage. Pinot noir was a usurper. Shiraz was at its peak of powerful domination, with the styles ever enlarging into the often-brutish wines of the 80s, 90s and 00s, while pinot was light and fragrant. They were polar opposites. You liked one or the other, but not both.

But the varieties actually have a noble history of sharing the same bottle, being paired in a uniquely Australian blend – in the Hunter Valley – that was all but forgotten until a somewhat recent revival.

There was a time when Australian wines were appended with famous names to both lend them lustre and convey style, which has also created much confusion. Hunter Valley Chablis was naturally never actual Chablis, but nor was it chardonnay. Hunter Valley riesling bottlings were not riesling either. Both, in fact, were semillon, with the monikers an attempt to capture style.

By car, the Hunter Valley is two hours north of Sydney. Photo by Elfes Images.

“Hunter Valley (or Hunter River) Burgundy” is also a term that was often used, both as a general reference and on front labels for shiraz-based wines, before the French thankfully put their foot down and called the lawyers in – allowing both the old and the new world to shine for what they did, and not holding up one as a foggy mirror of the other.

Although it is a somewhat warm zone for viticulture, the Hunter typically made reds of middling weight, often with a savoury, earthy fragrance. Those wines were deemed to fit into what were the ‘Burgundy Classes’ at wine shows of the times, with the ‘Claret Classes’ reserved for more structured wines that more readily recalled the wines of Bordeaux.

The three major players in the Hunter Valley in the mid-20th century – and still the icons today – were Lindeman’s, Tyrrell’s and Mount Pleasant. It was Lindeman’s who most famously wore the Burgundy tag, with ‘Hunter River Burgundy’ appended with a bin number on their labels – ‘Hunter River Chablis’, ‘Hunter River White Burgundy’ and ‘Hunter River Riesling’ also featured.

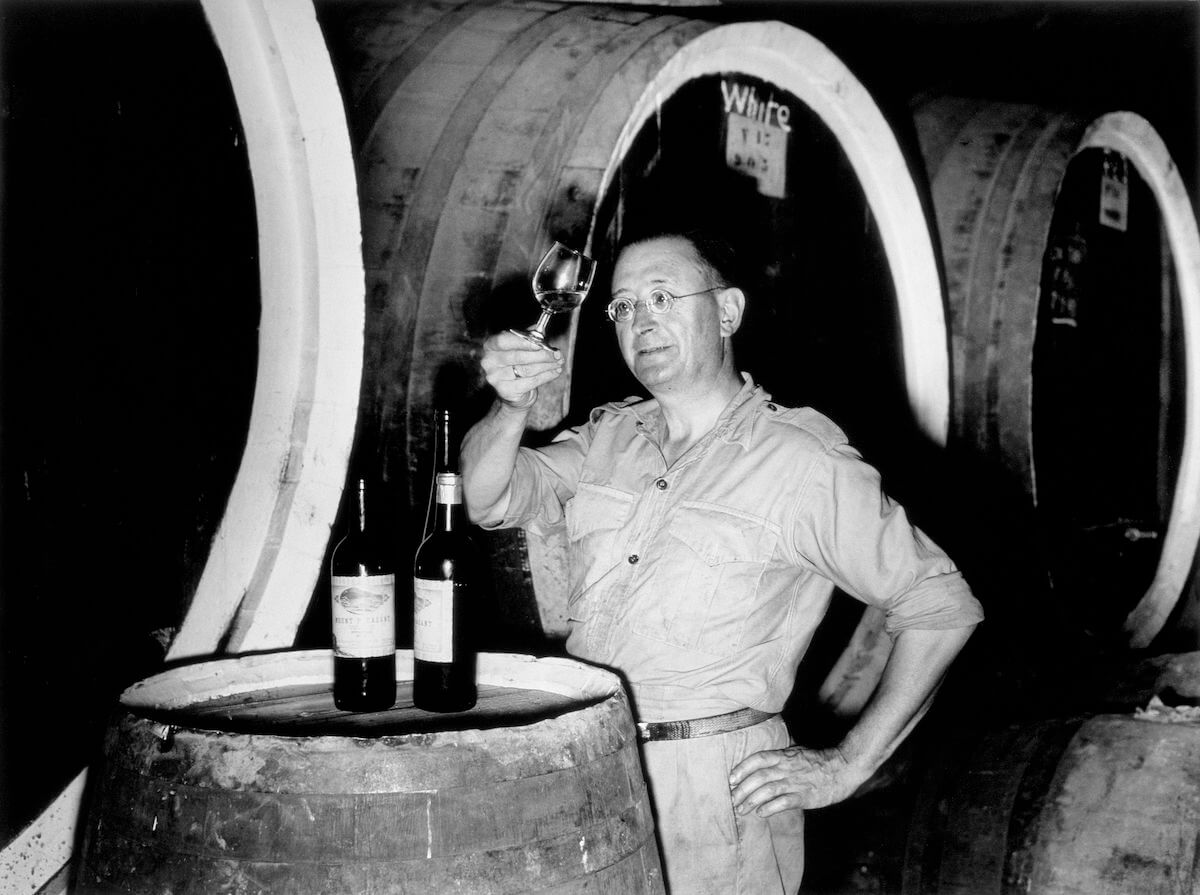

One of Australia’s greatest winemakers and pioneering viticultural thinkers was Maurice O’Shea of Mount Pleasant. He died too early, in 1956 aged 58, but his legacy is clearly still vibrantly apparent. At a time when fortifieds ruled the market, O’Shea championed table wines from the 30s through the 50s. And his efforts helped to shape the wine industry that we know today.

Maurice O’Shea, described in the biography by Campbell Mattinson as, “The greatest winemaker Australia has known”.

Mount Pleasant claims to have Australia’s oldest pinot noir vines – down to two rows now – and is the source of one of this country’s most revered clones: MV6 or Mothervine 6 (purportedly sourced from the Burgundy Grand Cru Clos de Vougeot). Today, MV6 is especially prevalent in Victorian vineyards. Many may be surprised that the Hunter Valley is the cradle of Australian pinot noir, but it is.

O’Shea often put pinot to work in his shiraz bottlings, though generally anonymously. He also frequently used white grapes to achieve the weight and aromatic profile that he desired, fermenting red grapes on white skins and sometimes vice versa. The idea of blending grapes was not new, as distinguishing between varieties would not have been seen as that important previously. Rather, it would have been all one crop to make one wine or so.

O’Shea took things a step further, using the raw materials to create light and shade, focusing on the differences of varieties and the vagaries of sites. And this was with the most primitive of equipment, and with no electricity. He was a visionary, and a tenacious one at that.

In the 40s, pinot took an emphatic place in O’Shea’s famous ‘Light Dry Red’. That most iconic blend of shiraz and pinot was the Mount Pleasant ‘Mount Henry’ bottling – there were varietally labelled blends, too, though the location-specific synonym of the day for shiraz, Hermitage, was used. (There is no actual Mount Henry, rather it is an homage to O’Shea’s friend and ardent supporter of his wines, restaurateur Henri Renault, chef and owner of l’Hermitage in Sydney.)

While we think of pinot noir being the lighter and less structured of the two grapes, it is an earlier ripener, so it has the opportunity to reach both flavour and tannin maturity more readily than shiraz. Additionally, the MV6 Clone is one of the more robustly fruited, with a strong tannic line, which is particularly emphasised in the Hunter. Needless to say, a Hunter pinot looks nothing like a Mornington pinot. So, it can contribute structure and depth of flavour rather than diluting either attribute, and it is said to have actually bolstered the shiraz in cooler years.

Early in his career, long-serving winemaker Karl Stockhausen was responsible for making two of Lindeman’s most famous red wines. They were the legendary ‘Hunter River Burgundy’ pair of ‘Bin 3100’ and ‘Bin 3110’. Both were from the 1965 vintage and harvested significantly later than normal.

It was known that pinot noir was blended into one of the wines, though not which or how much. Over the years, this presence of pinot took on mythical proportions. In reality, a small pinot plot was blended into the ‘Bin 3100’, and only accounted for 0.5 per cent of the wine – hardly a decisive inclusion. Nonetheless, a legacy started by the great O’Shea was given more life, and the style an even more legendary aura.

The Hunter Valley Burgundy style, which was very much the product of the mid-20th century was always fundamentally shiraz. Some would have included a parcel of pinot here and there, sometimes out of conscious blending decisions, and sometimes because there was some pinot that needed to go somewhere, but the true pinot shiraz blends were the province of O’Shea.

It’s worth noting that, anecdotally, the Hunter had more pinot noir in the ground in the 30s and 40s (relative to shiraz), as well as meaningful amounts of pinot meunier. The more reliable, more regionally apt variety soon held sway, and now pinot represents about 3 per cent of the size of the shiraz plantings.

When O’Shea died, the ‘Mount Henry’ label faded into history, along with the blend. Though it was quietly resurrected after much urging from long-time Chief Winemaker Phil Ryan. The first modern release was the 1998, and a 2002 was also made. But it was the next release that made the impact, the 2011, which was also the same year that Mount Pleasant released their first varietal pinot noir since 1996. Both 2011s were made by Gwyn Olsen, who now works with both Pepper Tree Wines and Briar Ridge – and both now make versions of O’Shea’s blend.

A few year later, the blend was then vocally championed by Chief Winemaker Jim Chatto. It was also Chatto who resurrected many of O’Shea’s individual parcel bottlings, too, reviving what was then a very uncommon practice of focusing on site, rather than regional style.

That 2011 was the start of the Hunter’s renaissance of the blend, with Meerea Park following in 2013, and makers like Silkman, Usher Tinkler and Comyns & Co., amongst others, following suit. Hunter winemakers also imported the style down south, notably to the Yarra Valley, with Simon Steele of Medhurst and Sarah Crowe of Yarra Yering leading the way. Medhurst’s ‘YRB’ wine even carries a cheeky nod to the Hunter‘, with the acronym standing for ‘Yarra River Burgundy’.

Crowe made the first ‘Light Dry Red’ at Yarra Yering from the 2015 vintage, which was both a tribute to a long-retired style made by the late Dr Bailey Carrodus – Yarra Yering’s founder – and those early wines of O’Shea. It was somewhat of a breakout wine for the style, making a big impression critically and inspiring other makers to experiment with the blend.

Crowe notes that the makers in the Hunter generally have the intent of producing medium-bodied wines that will age well, usually with shiraz the dominant component. They will often use a little more new oak and see a seriousness to the blend that is perhaps not so widely taken up in places like the Yarra, where a close to equal blend is more likely, and early approachability and crunchy vibrancy are the order of the day – though not exclusively. And the latter is her approach, though with a decent nod to the former, too.

“Firstly, I look for balance, but for me I don’t want it to be simple and fruity and confected. I want it to be soft and juicy, and you think, ‘that’s really slurpy and I want another glass,’ but then you notice the structure to it. And you think, ‘hang on a minute, it’s more spicy, more complex, there’s more longevity – this wine has more legs than I thought it did.’ It’s about building all those things in.”

That principle may just indeed be a distant reflection of how O’Shea crafted his wines, with an eye firmly on a more complete whole. Perhaps in a lighter frame, but with an eye to detail, drinkability and potentially age-worthiness. And it’s worth noting that those wines of O’Shea stood the test of time, too, drinking spectacularly – by all reports – 60 years later. The wines that many winemakers are making today, outside of pure curiosity, are very much tributes to those early wines of O’Shea. And in the absence of readily accessible liquid examples, it’s an old idea seen through a brand-new lens.

The grapes

Pinot noir and shiraz, or syrah if you prefer, are anchored in the French regions of Burgundy and the Northern Rhône respectively. Pinot noir is naturally grown very successfully further north in Champagne and syrah is grown in the Southern Rhône, and elsewhere, but those are the pinnacle old world regions for table wines. And they’re not that far apart geographically. The grapes, however, were always seen to be exclusively individual cultivars – products of different genetic lineages. It seems, though, that they have a closer relationship than that, with the preeminent grape geneticist Dr José Vouillamoz’s research pointing to pinot being a likely “great-grandparent” of syrah.

Genetic links notwithstanding, an experienced taster is unlikely to confuse the two, even when they meet close to the middle, with shiraz at its most fragrant and pinot at its most brooding. In broad brushstrokes, pinot will tend to the fragrant and perfumed with red fruits predominating, while shiraz will tend to darker fruits with more robust spice notes and more tannic grip. But that middle ground is where blending starts to make some sense. Blending like with like increases volume but not necessarily interest or detail. Blending with a mixture of the complementary and the contrasting starts to build layers, to build character. The way the structure is arranged and the fruit complexity etc., keeping in mind that both varieties must at least be moderately successful in their region.

You can read the entire article here at Young Gun of Wine.